Deobfuscating Javascript via AST: Constant Folding/Binary Expression Simplification

Preface

This article assumes a preliminary understanding of Abstract Syntax Tree structure and BabelJS. Click Here to read my introductory article on the usage of Babel.

What is Constant Folding?

Constant Folding: “An optimization technique that eliminates expressions that calculate a value that can already be determined before code execution.” (Source)

To better explain constant folding, it’s perhaps more useful to first introduce the obfuscation technique that constant folding fights against. Take the following code for example:

Examples

Example #1: The Basic Case

1 | |

An obfuscator may split each constant value into multiple binary expressions, which could look something like this after obfuscation:

1 | |

As you can see, the obfuscation has transformed what used to be easy to read constants; 27, 4, "I am a string literal, totally whole!" ; into multiple expressions with arithmetic and bitwise operators. The code is even using mathematical operators on booleans! Someone reading the code would likely need to evaluate each expression in a debugger to figure out the value of each variable. Let’s paste the second snippet in the dev tools console to check:

We can observe that each variable in the second snippet has an equivalent ability to that of its first snippet counterpart. The way the javascript engine simplified the expressions down to a constant is the essence of Constant Folding.

Now, hypothetically, you could just evaluate each expression in a javascript interpreter and replace it by hand manually. And sure, you could do that in just a few seconds for the snippet I provided. But that isn’t a feasible solution if there were hundreds or even thousands of lines of code in a program similar to this. Thankfully for us, Babel has an inbuilt feature that can help us automate the simplification.

Analysis Methodology

Let’s start by pasting the obfuscated sample into AST Explorer

If we click on one of the expression chunks on the right-hand side of the assignment expressions, we can take a closer look at the AST structure:

We can see that in this case, the small chunk of the string is of type StringLiteral, and it’s contained inside a bunch of nested BinaryExpression nodes. If we look at any other fraction of the other expressions, we can observe two important commonalities

A constant value, or Literal (e.g. StringLiteral,NumericLiteral, or BooleanLiteral)

The Literal is contained inside a single or nested BinaryExpression(s).

Our final goal is to evaluate all the binary expressions to reduce each right-hand side expression to a constant Literal value. Based on the nested nature of the BinaryExpressions, you might be thinking of manually writing a recursive algorithm. However, there’s a much simpler way to accomplish the same effect using Babel’s inbuilt path.evaluate() function. Here’s how we’re going to use it:

- Traverse through the AST to search for BinaryExpressions

- If a BinaryExpression is encountered, try to evaluate it using

path.evaluate(). - Check if it returns

confident:true. Ifconfidentisfalse, skip the node by returning. - Create a node from the value using

t.valueToNode(value)to infer the type, and assign it to a new variable,valueNode - Check that the resulting

valueNodeis a Literal type. If the check returnsfalseskip the node by returning.- This will cover StringLiteral, NumericLiteral, BooleanLiteral etc. types and skip over others that would result from invalid operations (e.g.

t.valueToNode(Infinity)is of type BinaryExpression,t.valueToNode(undefined)is of type identifier)

- This will cover StringLiteral, NumericLiteral, BooleanLiteral etc. types and skip over others that would result from invalid operations (e.g.

- Replace the BinaryExpression node with our newly created `valueNode’.

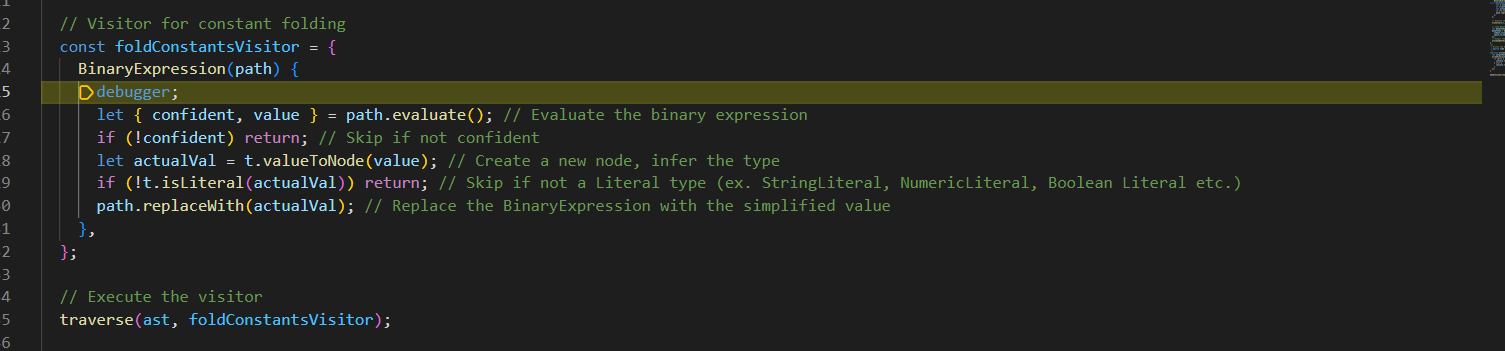

The babel implementation is shown below:

Babel Deobfuscation Script

1 | |

After processing the obfuscated script with the babel plugin above, we get the following result:

Post-Deobfuscation Result

1 | |

And the original code is completely restored!

Example #2: A Confident Complication

If you’ve read my article on String Concealing, specifically the section on String Concatenation, you may know that you can encounter a problem using the babel script above.

Let’s say you have a code snippet like this:

1 | |

By manual inspection, you can probably deduce that it can be reduced to this:

1 | |

However, if we try running the deobfuscator we made above against the obfuscated snippet, it yields this result:

1 | |

It hasn’t been simplified at all! But why?

Where The Issue Lies

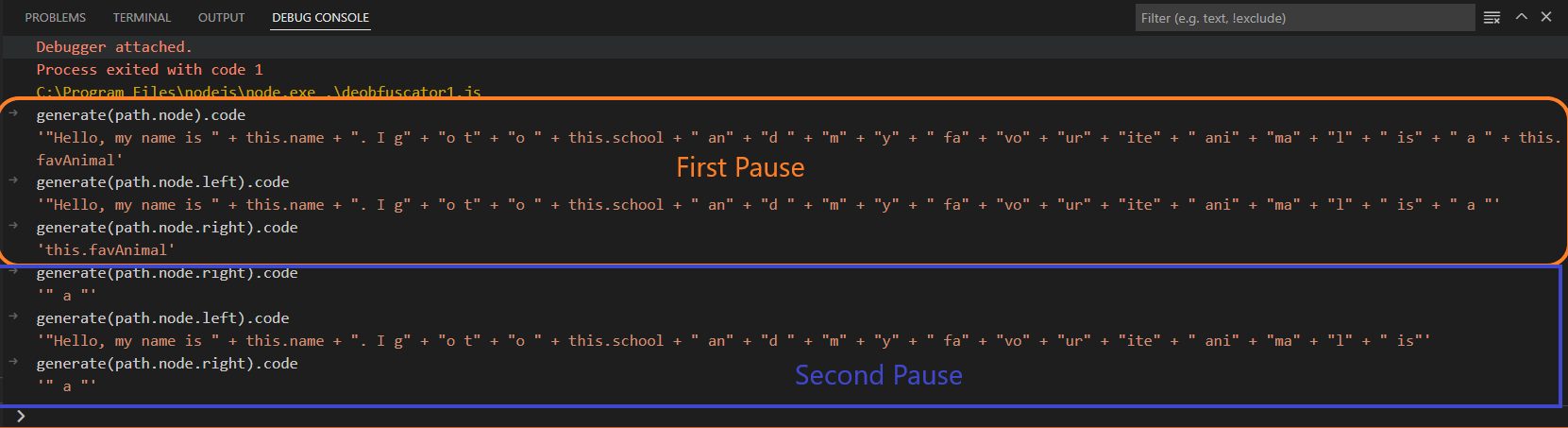

To figure out what the problem is, let’s use a debugger and set breakpoints to try and understand what our deobfuscator is actually doing.

We know that our visitor is acting on nodes of type BinaryExpression. A binary expression always has 3 main components: a left side, a right side, and an operator. For our example, the operator is always addition, +. On each iteration, let’s run these commands in the debug console to check what our left and right side are.

generate(path.node).codegenerate(path.node.left).codegenerate(path.node.right).code

Below is a screencap of what the first two iterations would look like:

When the visitor is first called, path.evaluate() will not return a value and the confident return value will be false. A false value for confident arises when the expression to be evaluated contains a variable whose value is currently unknown, and therefore Babel cannot be “confident” when attempting to compute an expression containing it. In the case of the first expression, the unknown variable (this.favAnimal) on the right side of the expression, and two unknown variables: (this.name & this.school) on the left side of the expression prevent path.evaluate() for returning a literal value. When the debugger statement is reached for a second time, the right-hand side of the expression is a StringLiteral ("a"). However, the left-hand side still contains variables with an unknown value. If we were to continue this for each time the breakpoint is encountered, the structure would look like this:

| Iteration | Left Side | Operator | Right Side |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ + “m” + “y” + “ fa” + “vo” + “ur” + “ite” + “ ani” + “ma” + “l” + “ is” + “ a “ | + | this.favAnimal |

| 2 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ + “m” + “y” + “ fa” + “vo” + “ur” + “ite” + “ ani” + “ma” + “l” + “ is” | + | “ a” |

| 3 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ + “m” + “y” + “ fa” + “vo” + “ur” + “ite” + “ ani” + “ma” + “l” | + | “ is” |

| 4 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ + “m” + “y” + “ fa” + “vo” + “ur” + “ite” + “ ani” + “ma” | + | “l” |

| 5 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ + “m” + “y” + “ fa” + “vo” + “ur” + “ite” + “ ani” | + | “ma” |

| 6 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ + “m” + “y” + “ fa” + “vo” + “ur” + “ite” | + | “ ani” |

| 7 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ + “m” + “y” + “ fa” + “vo” + “ur” | + | “ite” |

| 8 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ + “m” + “y” + “ fa” + “vo” | + | “ur” |

| 9 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ + “m” + “y” + “ fa” | + | “vo” |

| 10 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ + “m” + “y” | + | “ fa” |

| 11 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ + “m” | + | “y” |

| 12 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ | + | “m” |

| 13 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” | + | “d “ |

| 14 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school | + | “ an” |

| 14 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ | + | this.school |

| 14 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” | + | “o “ |

| 14 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” | + | “o t” |

| 14 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name | + | “. I g” |

| 14 | “Hello, my name is “ | + | this.name |

It’s evident that at every encounter, one of the sides will always contain a variable of unknown value. Therefore, path.evaluate() will return confident: false and be useless in simplifying the expression. So, we’ll need to try something else.

Constructing the Solution

Idea #1: Prioritizing Chunks of Consecutive Literals

We know that the issue lies with one of the sides containing a variable. However, we can see that there are chunks of the code that contain consecutive string literals only:

1 | |

If there were some way to prioritize these smaller chunks, then surely path.evaluate() would be able to simplify them. This is indeed the case, as we can prove this by manually wrapping each of these chunks in parentheses to force them to be evaluated first:

1 | |

Running this through the deobfuscator, we get our desired result:

1 | |

Alright, so that did the job. But for very long binary expressions which you might encounter in wild obfuscated scripts, you certainly do not want to have to spend time manually wrapping chunks of consecutive strings in parentheses. Sure, you could probably automate it with Regex, or write an AST-based algorithm to add brackets to the source string, but there has to be a less complicated way, right?

The answer: Yes, there is. And we are on the right track.

Idea #2: Even Smaller Chunks

Okay, so we know that trying to pinpoint and prioritize chunks of consecutive strings with varying lengths can be troublesome. But what if we just split the binary expression into the smallest possible pieces and prioritized those?

I’ll admit, that probably sounds confusing. So I’ll do my best to explain what I mean with an example.

We know that a binary expression, in its simplest form, consists of a left side, an operator, and a right side. Let’s refer back to the first three rows of the table we made:

| Iteration | Left Side | Operator | Right Side |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ + “m” + “y” + “ fa” + “vo” + “ur” + “ite” + “ ani” + “ma” + “l” + “ is” + “ a “ | + | this.favAnimal |

| 2 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ + “m” + “y” + “ fa” + “vo” + “ur” + “ite” + “ ani” + “ma” + “l” + “ is” | + | “ a” |

| 3 | “Hello, my name is “ + this.name + “. I g” + “o t” + “o “ + this.school + “ an” + “d “ + “m” + “y” + “ fa” + “vo” + “ur” + “ite” + “ ani” + “ma” + “l” | + | “ is” |

The right side of our binary expression is always only one element long, and is either a literal value or an identifier. However, the left side isn’t a single element long. Rather, it’s also a binary expression, containing both literal values and identifiers. What I propose is developing an algorithm to ensure that both the left side and right side are only a single element long. Then, if both are string literals, we can concatenate them. If not, we can simply move on.

To do this, let us look at the above table again, but only the first two rows. However, for the left side, let’s only take into consideration the right-most edge of the expression. That would look something like this:

| Iteration | Right Edge of Left Side | Operator | Right Side |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | this.favAnimal | |

| 2 | + | “ a” |

If we were to evaluate these now, we would observe the following:

- Row 1 still cannot be evaluated, since it is a

StringLiteral+a variable of unknown value. - Row 2 can be simplified into a single string literal:

" is" + " a"=>" is a"

We can then replace the right-most edge of the left side with the simplified result, so it will become the right side in the next iteration. This way, we can simplify consecutive concatenation of strings step by step. Keep in mind, that each simplification will affect the next iteration’s right side. The reason I included the first few rows and not the third, is because the simplification in the second iteration would change the right side of the third iteration, so it would no longer look like the original table.

Following the new algorithm, each iteration of our visitor would look like this:

| Iteration | Right Edge of Left Side | Operator | Right Side |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | “ a “ | + | this.favAnimal |

| 2 | “ is” | + | “ a” |

| 3 | “l” | + | “ is a” |

| 4 | “ma” | + | “l is a” |

| 5 | “ ani” | + | “mal is a” |

| 6 | “ite” | + | “ animal is a” |

| 7 | “ur” | + | “ite animal is a” |

| 8 | “vo” | + | “urite animal is a” |

| 9 | “ fa” | + | “vourite animal is a” |

| 10 | “y” | + | “ favourite animal is a” |

| 11 | “m” | + | “y favourite animal is a” |

| 12 | “d “ | + | “my favourite animal is a” |

| 13 | “ an” | + | “d my favourite animal is a” |

| 14 | this.school | + | “ and my favourite animal is a” |

| 14 | “o “ | + | this.school |

| 14 | “o t” | + | “o “ |

| 14 | “. I g” | + | “o to “ |

| 14 | this.name | + | “. I go to “ |

| 14 | “Hello, my name is “ | + | this.name |

So, by following this algorithm, we should be able to combine all consecutive string literals into one.

WAIT! There’s something wrong here…

The line of code we start with is let helloStatement = "Hello, my name is " + this.name + ". I g" + "o t" + "o " + this.school + " an" + "d " + "m" + "y" + " fa" + "vo" + "ur" + "ite" + " ani" + "ma" + "l" + " is" + " a " + this.favAnimal;

We know that on the second iteration, " is" and " a" will be concatenated into a single string literal, then the right-most edge of the left side will be replaced with the resulting value. That is,

" is" => " is a"

The problem here is that we are adding the right side of the expression to the right edge of the left side of the expression. However, the original right side remains unchanged despite already being accounted for. The code after one iteration would then look like this:

let helloStatement = "Hello, my name is " + this.name + ". I g" + "o t" + "o " + this.school + " an" + "d " + "m" + "y" + " fa" + "vo" + "ur" + "ite" + " ani" + "ma" + "l" + " is a " + " a " + this.favAnimal;

Notice the extra duplicate near the end, " is a " + " a ". To fix this, we need to ensure that we delete the original right side of the expression after doing the concatenation and replacement.

So, based on this logic, the correct steps for creating the deobfuscator are as follows:

Writing The Deobfuscator Logic

Traverse the ast in search of BinaryExpressions. When one is encountered:

- If both the right side (

path.node.right) and the left side (path.node.left) are of type StringLiteral, we can use the algorithm for the basic case. - If not:

- Check if the right side, (

path.node.right) is a StringLiteral. If it isn’t, skip this node by returning. - Check if the right-most edge of the left-side (

path.node.left.right) is a StringLiteral. If it isn’t, skip this node by returning. - Check if the operator is addition (

+). If it isn’t, skip this node by returning. - Evaluate the right-most edge of the left-side + the right side;

path.node.left.right.value + path.node.right.valueand assign it’s StringLiteral representation to a variable,concatResult. - Replace the right-most edge of the left-side with

concatResult. - Remove the original right side of the expression as it is now a duplicate.

- Check if the right side, (

- If both the right side (

The Babel implementation is as follows:

Babel Deobfuscation Script

1 | |

After processing the obfuscated script with the babel plugin above, we get the following result:

Post-Deobfuscation Result

1 | |

And all consecutive StringLiterals have been concatenated! Huzzah!

Conclusion

Okay, I hope that second example wasn’t too confusing. Sometimes, you’ll be able to avoid the problem with unknown variable values by replacing references to a constant variable with their actual value. If you’re interested in that, you can read my article about it here. In this case, however, it was unavoidable due to being within a class definition where variables have yet to be initialized.

Keep in mind that the second example will only work for String Literals and addition. But, it can easily be adapted to other node types and operators. I’ll leave that as a challenge for you, dear reader, if you wish to pursue it further 😉

If you’re interested, you can find the source code for all the examples in this repository.

Anyways, that’s all I have for you today. I hope that this article helped you learn something new. Thanks for reading, and happy reversing!